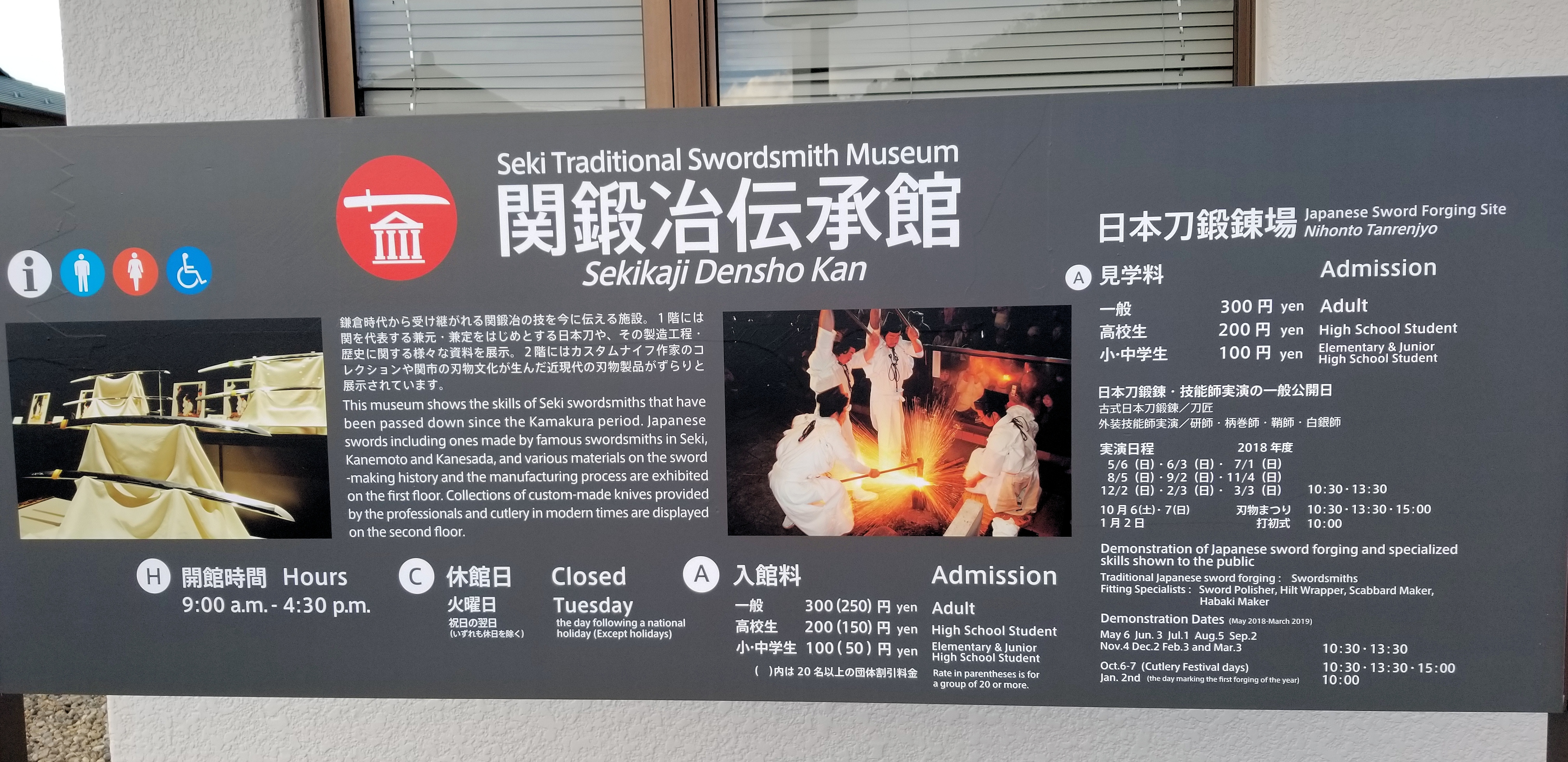

The beautiful city of Seki, located in Gifu Prefecture has been a hub of bladesmithing for over 800 years, emerging alongside the rise of the Samurai warrior caste. Perfectly nestled between two rivers, Seki has an abundant supply of river clay and coal which are ideal in the bladesmithing process.

Today Seki, Japan is one of the world’s leading producers of knives and cutlery, in close competition with Sheffield, England, and Solingen, Germany. To understand how this city became a powerhouse of pocket knives and kitchen cutlery, we must dive deep into its rich past of sword making.

The

Japanese sword that we are most familiar with was created in the 11th

century and experienced a golden age of craftsmanship in the 13th

century, with Japan’s most famous swordsmith, Masamune. This great master is

largely responsible for pioneering techniques in the crafting of Japanese

swords, without whom we would not have seen the flourishing of Seki as a center

for swordsmiths.

Masamune lived approximately from 1264 to 1343 A.D., at the height of the Kamakura period. During his career, Japan had to prepare for an invasion by the Mongols for the third time, making sword production even more relevant. Emperor Fushimi, greatly impressed with Masamune’s work, appointed him chief sword maker in 1287. Later he ran the Soshu school for bladesmiths, where he took on only ten students himself.

Sword making in Seki can be traced back to Motoshige, the pioneer of Seki swordmaking, who moved from the Kyushu district to Seki sometime between 1229-1261. Masamune’s legacy also took root in Seki in the 14th century with two of his ten students, Kaneuji and Kinju, who made swords in the Mino style. Once becoming masters themselves, Kaneuji and Kinju went on to teach in Seki, founding their own school and creating new traditions in sword making that would be the long-standing foundations for the next 600 years of bladesmithing.

The contemporary work

laid down by Kaneuji and Kanju grew in importance during the latter part of the

14th century, as the previously-closed Japanese market began exports

to the Ming dynasty. It is estimated that 100,000 swords were sold to China in

this period. Increased desire for finely-made blades drove fierce competition

for swordsmiths, with the Mino smiths prospering greatly.

Near the tail end of

the Muromachi Period (1392-1573) after the Onin war and the fall of the

Muromachi Shogunate, military generals began their fight for power, bringing

about a feudal warring period. With various factions clamoring for control over

regions of Japan, these leaders needed weapons—lots of weapons.

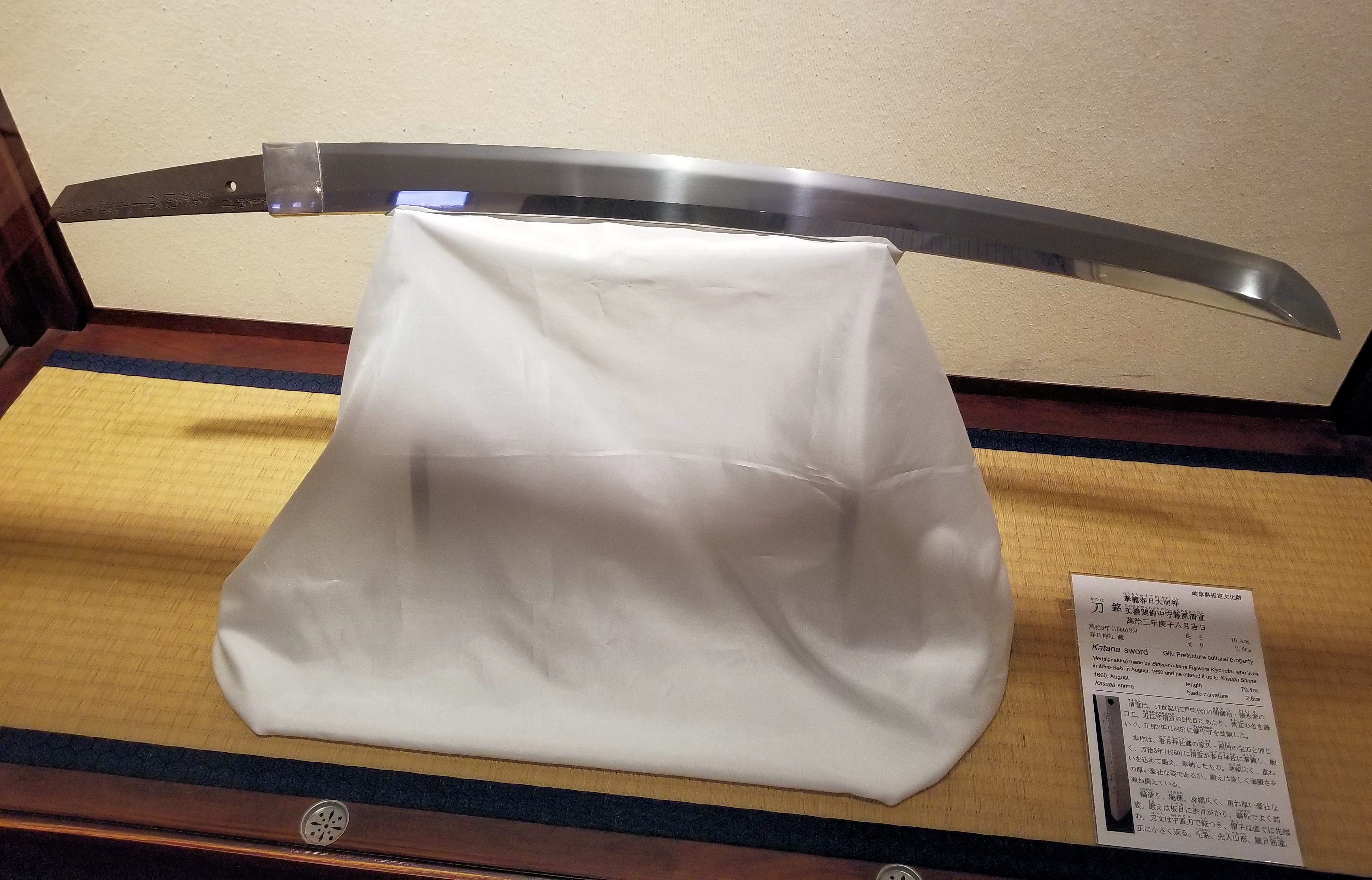

Common characteristics of Mino smiths’ swords, such as thin layers of steel with distinct jagged patterns on the Hamon (sharpened edge of the blade) added to the appeal of their swords due to their practicality and beauty. These blades were so well renowned that many feudal Lords desired to use them exclusively.

There were more than 300

swordsmiths working in Seki during the Muromachi Era of 1338-1573. Among the most

famous were Kenemoto Magoroku and Saburo Shizu. The Seki reputation was firmly

established and recognized throughout Japan. In the words of one samurai, the Seki

katana “Doesn’t bend. Doesn’t break, Cuts well.”[1]

In the West the use of blades

as the primary weapon of choice fell drastically with the rise of firearms in

the early modern period, swords became largely ceremonial in purpose. Seki

continued primarily to produce swords until the industrial revolution. Sword

fighting was considered a more honorable way to engage in combat under the

strict Bushido code, which dissuaded the use of firearms.

The great shift from

swords to shorter blades, practical knives and cutlery occurred in the 1850’s

when trade policies opened ports to western consumers. Katanas and other swords

were still made, but the demand had gradually fallen at the turn of the 20th

century.

Master smiths in Japan faced a new trial by the end of World War II,

General MacArthur banned not only the making of Katanas, but merely possessing

one. With new laws in effect, many craftsmen turned to making kitchen cutlery,

which had high demand abroad, as well as scissors and other types of blades. Traditional

forging processes and western style blades brought about a new market for

practical blades with exceptional quality that are still sought after today.

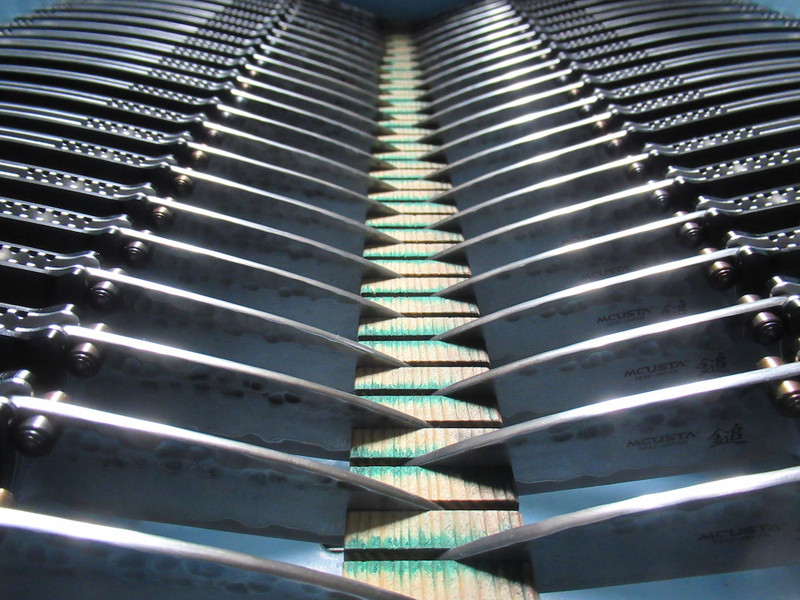

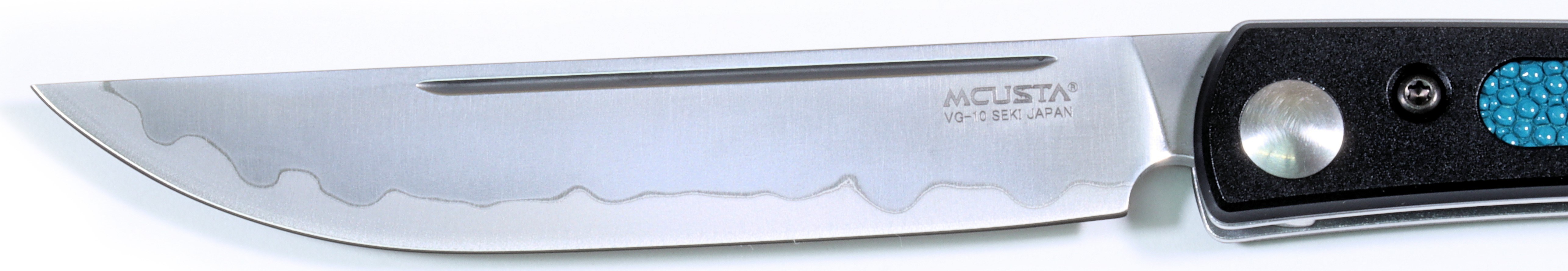

Currently, in 2022, the Seki Cutlery Association has sixty members and Marusho Industry is a proud member of this organization. Marusho produces Silky scissors, Mcusta folding knives and Zanmai kitchen knives – all with the strictest quality control and excellent materials. While high tech machinery is more in use today, a portion of the process is still hand done with great care and attention to detail. The top-quality knives from Mcusta are bought all over the world and will continue to captivate buyers with their beautiful designs well into the future.

There are still master bladesmiths forging swords through the tech age, however, there are only ten traditional licensed bladesmiths allowed by the Japanese government to produce Katanas. Each master may only make two swords a month. One such family continuing the art of sword making is the Fujiwara family, which currently has two members making traditional swords as 25th and 26th generation swordsmiths. The practical use of Katanas has all but disappeared, but this craft continues on and many are bestowed to the Emperor or used to celebrate special events. Many hope that this artform will keep its place in the hearts of the next generation, as a way of remembering the past and the love of tradition.

_______________________

Sources:

“History of Japanese Knife Crafting,” Korin.com, accessed January 26, 2022, https://www.korin.com/about-history-of-japanese-knife-crafting.

“Introduction of SEKI – MCUSTA.” Accessed February 2, 2022. http://mcustaknives.com/about-us/seki/.

Kathleen

Kuiper, “Masamune Japanese Swordsmith,” Britannica, last modified

October 26, 2009, accessed January 26, 2022, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Masamune.

“Mino

Kinju,” Soshuden Museum, last modified November 16, 2019, accessed January 26,

2022, http://www.nihonto-museum.com/blog/mino-kinju.

Selena Hoy, “In the City of Blades,” Visit Gifu, accessed January 26, 2022, https://visitgifu.com/specials-of-gifu/seki-blades/.

“Shizu Saburo Kaeuji,” Nihonto.com, October 1, 2017, accessed January 26, 2022, https://www.nihonto.com/shizu-saburo-kaneuji-%E5%BF%97%E6%B4%A5%E4%B8%89%E9%83%8E%E5%85%BC%E6%B0%8F/.

“Masamune School,” www.jp.sword.com, accessed January 26, 2022, http://www.jp-sword.com/files/masamune/masamune.html.

“The Five Schools of the Japanese Sword-This will help you know the History of the Japanese Sword,” Tozando Co., Ltd, December 21, 2017, accessed January 31, 2022, https://weblog.tozando.com/the-five-schools-of-the-japanese-sword-this-will-help-you-know-the-history-of-the-japanese-sword/.

Visit Seki Official Guide. “Visit Seki Official Guide.” Accessed February 2, 2022. https://visitseki.jp/.

Yurie Endo, “Study of Japanese Sword, 57| Part 2 of — 23 Sengoku Period Sword,” Study of Japanese Sword.com, July 15, 2019, accessed January 31, 2022,https://studyingjapaneseswords.com/tag/togari-ba/.

[1] “Visit Seki Official Guide.”

US Dollar

US Dollar